-

Black Chinned Hummingbird Nesting

By

-

Dan & Diane

True

Twenty-six Black-chinned hummingbird nests were observed over a

three year period by my wife, Diane, and I in Texas and New Mexico. Some nests

were in trees. Nesting platforms known as Hummingbird Houses served as sites for

other nests. Hummingbird Houses were installed under eaves, porch ceilings, and

covered patios. Twenty-six Black-chinned hummingbird nests were observed over a

three year period by my wife, Diane, and I in Texas and New Mexico. Some nests

were in trees. Nesting platforms known as Hummingbird Houses served as sites for

other nests. Hummingbird Houses were installed under eaves, porch ceilings, and

covered patios.

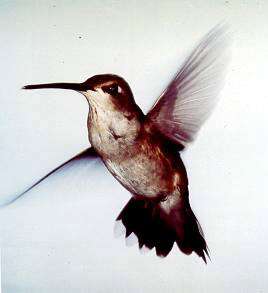

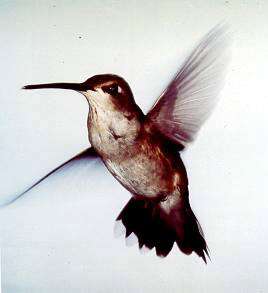

Migrating female hummingbirds follow males in spring

into the United States and Canada from wintering grounds in Mexico by three to

ten days. The birds come north for one purpose: to raise

young, and they waste no time in getting down to business. Nest construction

generally begins the day they arrive. Distended abdomens on some of the hens

indicated those little birds arrived impregnated. Migrating female hummingbirds follow males in spring

into the United States and Canada from wintering grounds in Mexico by three to

ten days. The birds come north for one purpose: to raise

young, and they waste no time in getting down to business. Nest construction

generally begins the day they arrive. Distended abdomens on some of the hens

indicated those little birds arrived impregnated.

|

|

|

This little hen

is so heavy with eggs we can't see her feet because they have been

absorbed by her

feathers. |

Top priority in a female hummingbird's mind for nest site

selection is: nest in a geographical area where temperatures are likely to

remain 96 degrees F or less throughout her nesting cycle.

Her reason is, she aims for an egg incubation temperature of 96 degrees. If the

temperature rises above 96 and remains above that level for several hours, (or

days) her eggs will "cook", killing the embryo. This probably explains why areas

where summer temperatures soar into the 100s see their arriving hummers

"disappear" in May. The little birds "disappeared" because they were really only

passing through on their way to cooler climate locations in our northern states

and Canada. Invariably the little rascals "reappear" in late July and early

August, and pause to show us their youngsters before humming on south to

wintering grounds in Mexico and Central America. A few Ruby-throats don't follow

the crowd and remain behind in hotter states. These birds are often found in

states with mountains high enough in altitude to experience a summer with less

harsh temperatures...the Ozark's and Appalachians, for example. (The air cools

at a rate of 5.5 degrees F per 1,000 feet rise in altitude.) However, a few

Ruby-throats remain at low altitudes in states that can sizzle in the summer.

These hardy souls have learned a unique way to escape egg cooking temperatures. Top priority in a female hummingbird's mind for nest site

selection is: nest in a geographical area where temperatures are likely to

remain 96 degrees F or less throughout her nesting cycle.

Her reason is, she aims for an egg incubation temperature of 96 degrees. If the

temperature rises above 96 and remains above that level for several hours, (or

days) her eggs will "cook", killing the embryo. This probably explains why areas

where summer temperatures soar into the 100s see their arriving hummers

"disappear" in May. The little birds "disappeared" because they were really only

passing through on their way to cooler climate locations in our northern states

and Canada. Invariably the little rascals "reappear" in late July and early

August, and pause to show us their youngsters before humming on south to

wintering grounds in Mexico and Central America. A few Ruby-throats don't follow

the crowd and remain behind in hotter states. These birds are often found in

states with mountains high enough in altitude to experience a summer with less

harsh temperatures...the Ozark's and Appalachians, for example. (The air cools

at a rate of 5.5 degrees F per 1,000 feet rise in altitude.) However, a few

Ruby-throats remain at low altitudes in states that can sizzle in the summer.

These hardy souls have learned a unique way to escape egg cooking temperatures.

The temperature within a stand of broadleaf trees will average 5

to 7 degrees cooler than open or urban areas. This is due to the tree's

transpiration, which provides natural, evaporative air conditioning within the

tree's umbrella. (An average oak transpires 50 gallons of

water per day.) A very small population of Ruby-throats have discovered this

natural phenomena and attempt to nest at altitudes where summer temperatures

almost always exceed 100. In those cases nests are often found on the low branch

of a broadleaf tree overhanging a body of water. Female Ruby-throats have

apparently found the thin layer of cool air created by evaporation from the

water's surface. That thin layer of cool air, combined with the tree's 5 to 7

degrees worth of cooling, creates a micro environment matching northern

climates. Note that hummingbirds migrate to nesting areas where humans go to

escape summer's heat...'way north, the mountains, or a lake. The temperature within a stand of broadleaf trees will average 5

to 7 degrees cooler than open or urban areas. This is due to the tree's

transpiration, which provides natural, evaporative air conditioning within the

tree's umbrella. (An average oak transpires 50 gallons of

water per day.) A very small population of Ruby-throats have discovered this

natural phenomena and attempt to nest at altitudes where summer temperatures

almost always exceed 100. In those cases nests are often found on the low branch

of a broadleaf tree overhanging a body of water. Female Ruby-throats have

apparently found the thin layer of cool air created by evaporation from the

water's surface. That thin layer of cool air, combined with the tree's 5 to 7

degrees worth of cooling, creates a micro environment matching northern

climates. Note that hummingbirds migrate to nesting areas where humans go to

escape summer's heat...'way north, the mountains, or a lake.

The rule for eastern states is, if you have females in June, it

is likely the birds are nesting with you. No females in June says they are

nesting elsewhere, and elsewhere is probably somewhere up

north. (In Arizona and southern California, Anna's

hummingbirds avoid egg cooking temperatures by choosing to nest in January and

February. Costa's hummingbirds avoid the desert heat by humming up to nest in

those state's mountains.) The female's second priority for nest location is:

Find a place out of the wind. The rule for eastern states is, if you have females in June, it

is likely the birds are nesting with you. No females in June says they are

nesting elsewhere, and elsewhere is probably somewhere up

north. (In Arizona and southern California, Anna's

hummingbirds avoid egg cooking temperatures by choosing to nest in January and

February. Costa's hummingbirds avoid the desert heat by humming up to nest in

those state's mountains.) The female's second priority for nest location is:

Find a place out of the wind.

The importance of selecting a nest site that is protected from

the wind was emphasized from the experience of Jay and Carrie Hollifield of

Roswell, New Mexico. Winds catapulted ten hummingbird eggs

out of five nests from elm branches in their ranch yard in 1999. In Amistad, New

Mexico, broken hummingbird eggs were often found on the ground by Dave Dunnigan

after strong winds raked his ranch yard. 8 to 10 Black-chinned hummingbirds nest

around Dunnigan's place each year. One of his little hens was so determined to

nest out of the wind she built down low, 18 inches above the ground, on a bush

snuggled in the shelter of a hen house. It is probable this bird was not a first

year mom, but rather an experienced mom who had suffered the consequences of

high winds in a previous nesting season. This suggests hummingbirds ae capable

of learning. In May of 2000, five of Dunnigan's hummers chose to nest on

Hummingbird Houses placed under his porch eaves, out of the wind. In Roswell,

Hummingbird Houses are installed at the Hollifield place, however a dozen pairs

of cliff swallows dominate choice nesting sites under their eaves. One of those

Hummingbird Houses was even taken over by swallows. The importance of selecting a nest site that is protected from

the wind was emphasized from the experience of Jay and Carrie Hollifield of

Roswell, New Mexico. Winds catapulted ten hummingbird eggs

out of five nests from elm branches in their ranch yard in 1999. In Amistad, New

Mexico, broken hummingbird eggs were often found on the ground by Dave Dunnigan

after strong winds raked his ranch yard. 8 to 10 Black-chinned hummingbirds nest

around Dunnigan's place each year. One of his little hens was so determined to

nest out of the wind she built down low, 18 inches above the ground, on a bush

snuggled in the shelter of a hen house. It is probable this bird was not a first

year mom, but rather an experienced mom who had suffered the consequences of

high winds in a previous nesting season. This suggests hummingbirds ae capable

of learning. In May of 2000, five of Dunnigan's hummers chose to nest on

Hummingbird Houses placed under his porch eaves, out of the wind. In Roswell,

Hummingbird Houses are installed at the Hollifield place, however a dozen pairs

of cliff swallows dominate choice nesting sites under their eaves. One of those

Hummingbird Houses was even taken over by swallows.

Nests we observed were established in places providing as much

wind protection as was available. They were sheltered either by an outer

perimeter of trees, or by buildings. Six to twelve feet

above the ground in the first row of inner branches where protection is

increased from weather elements were prevalent tree locations. Trees of choice,

in order of preference, were sycamore, fruitless mulberry, maple, elm, and

Russian olive. Note the larger the leaf, the higher the preference. Nests we observed were established in places providing as much

wind protection as was available. They were sheltered either by an outer

perimeter of trees, or by buildings. Six to twelve feet

above the ground in the first row of inner branches where protection is

increased from weather elements were prevalent tree locations. Trees of choice,

in order of preference, were sycamore, fruitless mulberry, maple, elm, and

Russian olive. Note the larger the leaf, the higher the preference.

A fork in a branch about 18 inches from its end was a repeating

tree nest location. The chosen branch averaged 1/4" in diameter...too small to

support a cat, but dangerously whippy in high winds. A

hen's search image includes the coincidence of either a large leaf or a cluster

of leaves three inches or less directly above the fork. She utilizes this leafy

"umbrella" to protect her nest against sun and rain, and to shield her eggs and

chicks from prying predator eyes. A fork in a branch about 18 inches from its end was a repeating

tree nest location. The chosen branch averaged 1/4" in diameter...too small to

support a cat, but dangerously whippy in high winds. A

hen's search image includes the coincidence of either a large leaf or a cluster

of leaves three inches or less directly above the fork. She utilizes this leafy

"umbrella" to protect her nest against sun and rain, and to shield her eggs and

chicks from prying predator eyes.

Nest construction

averaged five days. She brings materials to her site at a rate of 34 trips per

hour. The little hen's first load of material is spider

webbing. She applies that material as a sticky foundation on the forked area of

her nest site. Thereafter, her sequence is orderly. She airlifts plant down or

other soft material in her beak and tucks it into the fork. After shaping and

molding that material, she flies in another load of spider webbing. Most often

she carries a glob of webbing clinging to the underside of her beak, under her

throat, and down across her breast. Transfer of the webbing onto her nest is

achieved by pressing her chin and breast against the nest and wiping the webbing

onto her work. Stickiness of spider webbing appeared to be the only element

binding the nest. Frame by frame scrutiny of video tapes revealed no sign that

she used her spittle as glue. In that regard, for her little system to produce

enough spittle to construct her nest seems beyond a hummingbird's physical

capacity. Nest construction

averaged five days. She brings materials to her site at a rate of 34 trips per

hour. The little hen's first load of material is spider

webbing. She applies that material as a sticky foundation on the forked area of

her nest site. Thereafter, her sequence is orderly. She airlifts plant down or

other soft material in her beak and tucks it into the fork. After shaping and

molding that material, she flies in another load of spider webbing. Most often

she carries a glob of webbing clinging to the underside of her beak, under her

throat, and down across her breast. Transfer of the webbing onto her nest is

achieved by pressing her chin and breast against the nest and wiping the webbing

onto her work. Stickiness of spider webbing appeared to be the only element

binding the nest. Frame by frame scrutiny of video tapes revealed no sign that

she used her spittle as glue. In that regard, for her little system to produce

enough spittle to construct her nest seems beyond a hummingbird's physical

capacity.

Bits of camouflage followed the spider webbing and were applied

to her work-in-progress. Another load of plant down was

followed by spider webbing followed by a bit of camouflage, and so on. Four

hours straight was usually her work schedule before she quit for the day. Some

of the little hens worked mornings, others were afternoon types. Since

developing eggs burdens her with extra weight throughout nest building, it made

sense that she work on the nest no more than four hours per day. Bits of camouflage followed the spider webbing and were applied

to her work-in-progress. Another load of plant down was

followed by spider webbing followed by a bit of camouflage, and so on. Four

hours straight was usually her work schedule before she quit for the day. Some

of the little hens worked mornings, others were afternoon types. Since

developing eggs burdens her with extra weight throughout nest building, it made

sense that she work on the nest no more than four hours per day.

Concealing her work from its beginning is probably a reason the

female hummingbird camouflages her nest as she builds. One

hen was so picky about hiding her work that on the sun bleached side of a branch

she chose light colored camouflage material to match. On the shaded, and

therefore darker side of that same branch, she camouflaged that side of the nest

darker to match that side's coloration. Such attention to detail created a nest

that was camouflaged slightly differently on each side. Hummingbird House nests

were camouflaged against the color of the eave, ceiling, or patio cover where

the House was installed. Sometimes the hens gathered flakes of paint chips from

the building and applied the chips to their nest. A male bird was never seen

near a hummingbird nest. So, where is Daddy Bird during the female's flurry of

nest building activity? Concealing her work from its beginning is probably a reason the

female hummingbird camouflages her nest as she builds. One

hen was so picky about hiding her work that on the sun bleached side of a branch

she chose light colored camouflage material to match. On the shaded, and

therefore darker side of that same branch, she camouflaged that side of the nest

darker to match that side's coloration. Such attention to detail created a nest

that was camouflaged slightly differently on each side. Hummingbird House nests

were camouflaged against the color of the eave, ceiling, or patio cover where

the House was installed. Sometimes the hens gathered flakes of paint chips from

the building and applied the chips to their nest. A male bird was never seen

near a hummingbird nest. So, where is Daddy Bird during the female's flurry of

nest building activity?

Flashy gorgets transform Daddy Birds into Mr. Neon. To protect

her children from predators, the female would be foolish to tolerate a male

spotlighting her work during nest building, or during chick

raising. In whatever ways hummingbirds communicate, after

she has been impregnated, a probable reason we don't see hummingbird males near

hummingbird nests is that she has told Daddy Bird to take his brightly colored

flashy suit and hum off. Flashy gorgets transform Daddy Birds into Mr. Neon. To protect

her children from predators, the female would be foolish to tolerate a male

spotlighting her work during nest building, or during chick

raising. In whatever ways hummingbirds communicate, after

she has been impregnated, a probable reason we don't see hummingbird males near

hummingbird nests is that she has told Daddy Bird to take his brightly colored

flashy suit and hum off.

Molding the nest's

wall as the nest progresses upward was done by pressing the top edge between her

wing and body, as a potter shapes soft clay on a spinning

vase.

|

|

|

Hummingbird hen shaping her nest's edge between her wing and

body. |

Rounding the nest's inside was done by ramming her little

bottom, with tail feathers straight up, against inner

walls. She tamps the nest's floor by hanging on with one

foot and stomping rapidly with her free foot. Since her weight is about that of

a penny, hanging on with one foot and stomping with the other to pack the nest's

floor allows her leg muscle power to compensate for her light weight. She stops

work occasionally and simply sits in her nest, as if resting. The little hens

are so focused they ignore photo equipment moved in increments to as near to

them as five feet. One photo revealed a unique pattern in the structure of

hummingbird nests, a pattern that was previously unknown. Rounding the nest's inside was done by ramming her little

bottom, with tail feathers straight up, against inner

walls. She tamps the nest's floor by hanging on with one

foot and stomping rapidly with her free foot. Since her weight is about that of

a penny, hanging on with one foot and stomping with the other to pack the nest's

floor allows her leg muscle power to compensate for her light weight. She stops

work occasionally and simply sits in her nest, as if resting. The little hens

are so focused they ignore photo equipment moved in increments to as near to

them as five feet. One photo revealed a unique pattern in the structure of

hummingbird nests, a pattern that was previously unknown.

Backlighting a nest revealed that the lower half was thick and

dense while the upper half was thin enough to let some light

pass.

She probably incorporates this feature so that she can adjust air

circulation to maintain an egg incubation temperature of 96 degrees F, which is

5 degrees less than her normal body temperature. On cold days, she maintains egg

temperature by positioning her body below the thinner, upper half of the nests

walls hold warmth inside her nest. On hot days, raising her body above the

thinner portion of the nest's wall would increase air circulation and allow

excess egg incubation heat to escape. These smart little birds refine this

construction feature even more. Backlighting a nest revealed that the lower half was thick and

dense while the upper half was thin enough to let some light

pass.

She probably incorporates this feature so that she can adjust air

circulation to maintain an egg incubation temperature of 96 degrees F, which is

5 degrees less than her normal body temperature. On cold days, she maintains egg

temperature by positioning her body below the thinner, upper half of the nests

walls hold warmth inside her nest. On hot days, raising her body above the

thinner portion of the nest's wall would increase air circulation and allow

excess egg incubation heat to escape. These smart little birds refine this

construction feature even more.

For additional precision of egg temperature control, the

windward side of the upper wall is thicker than its lee

side. For additional precision of egg temperature control, the

windward side of the upper wall is thicker than its lee

side.

|

|

|

Nest with

thinner, almost "see through" upper wall on downwind side. Note side

facing camera, the side facing the prevailing wind, is

thicker. |

The "thickest" side of the upper wall invariably faces into

prevailing wind patterns.

That suggests she fashions the windward side of her

nest to give her eggs protection against the probing fingers of a cool wind.

Further, their first nests, those constructed in the relative cool of early

spring, have thicker and therefore warmer upper walls than second nests built in

summer. Another refinement in hummingbird nest building is that their spring

nests are deeper than their summer nests. On cool days the hens snuggled down so

deep inside their nests their beaks and tail aimed straight up. On warmer days

they sat so high in the nest and were fully visible. The eggs in one nest were

"cooked" during a record heat wave that spawned eight straight days of high

temperatures ranging between 100 and 103 degrees F. Those eggs failed to hatch.

Sometimes a nest was only half finished before the hen laid her first egg. The "thickest" side of the upper wall invariably faces into

prevailing wind patterns.

That suggests she fashions the windward side of her

nest to give her eggs protection against the probing fingers of a cool wind.

Further, their first nests, those constructed in the relative cool of early

spring, have thicker and therefore warmer upper walls than second nests built in

summer. Another refinement in hummingbird nest building is that their spring

nests are deeper than their summer nests. On cool days the hens snuggled down so

deep inside their nests their beaks and tail aimed straight up. On warmer days

they sat so high in the nest and were fully visible. The eggs in one nest were

"cooked" during a record heat wave that spawned eight straight days of high

temperatures ranging between 100 and 103 degrees F. Those eggs failed to hatch.

Sometimes a nest was only half finished before the hen laid her first egg.

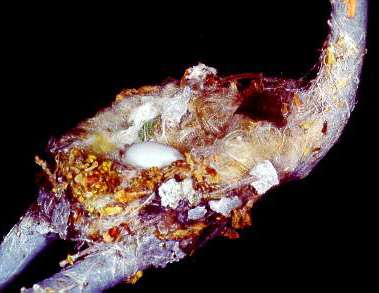

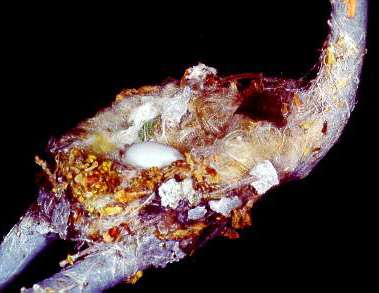

|

|

|

First egg

in a half finished

nest. |

Without exception, the hens skipped one day before laying their

second egg.

In proportion to body weight, hummingbird eggs are the largest

in the bird world. If human babies were proportional to hummer eggs, we would

give birth to 25 pound babies. A long handled mechanics mirror was used to check

a nest when a hen flew off to feed. Without exception, the hens skipped one day before laying their

second egg.

In proportion to body weight, hummingbird eggs are the largest

in the bird world. If human babies were proportional to hummer eggs, we would

give birth to 25 pound babies. A long handled mechanics mirror was used to check

a nest when a hen flew off to feed.  Activity was watched from a distance through

binoculars and a telescope. Clues that a hen was "in labor" came when she

settled on her nest and alternated between wiggling and shaking a few moments.

In one case we knew within ten minutes when a hen's first egg arrived. Activity was watched from a distance through

binoculars and a telescope. Clues that a hen was "in labor" came when she

settled on her nest and alternated between wiggling and shaking a few moments.

In one case we knew within ten minutes when a hen's first egg arrived.

|

|

|

New chick

with hatching nestmate. |

Incubation time on each nest was 14 days with one exception...a

12 day period in Texas. (That hen was smaller, and her

behavior different from other Black-chinns we observed. The hen may have been a

member of the smaller sub-species of Black-chinned Dr. Bill Baltosser believes

exists.) When the nest held eggs, it appeared the hen flew into and out of the

nest in a way that reduced the chance of downwash from her wings blasting an egg

out of her nest. In the split second during either launch or landing, she seems

to tilt her wings in a way that would direct her wing downwash away from the

nest's opening. In one nest it apeared that downwash from her hovering flight

ejected one egg, which crashed on the ground. The hen abandoned that nest and

its remaining egg. Incubation time on each nest was 14 days with one exception...a

12 day period in Texas. (That hen was smaller, and her

behavior different from other Black-chinns we observed. The hen may have been a

member of the smaller sub-species of Black-chinned Dr. Bill Baltosser believes

exists.) When the nest held eggs, it appeared the hen flew into and out of the

nest in a way that reduced the chance of downwash from her wings blasting an egg

out of her nest. In the split second during either launch or landing, she seems

to tilt her wings in a way that would direct her wing downwash away from the

nest's opening. In one nest it apeared that downwash from her hovering flight

ejected one egg, which crashed on the ground. The hen abandoned that nest and

its remaining egg.

Chick feeding intervals averaged twenty minutes. Without

exception the moms brooded their chicks through eight

nights. The ninth they spent somewhere other than on the

nest. Chicks at that age were feathered enough to regulate their own

temperatures. The two chicks were large enough by then that their little bodies

stretched the nest and filled it side to side, with their backs almost flush

with the nest's rim. This age, nine days, is the earliest observation of

youngsters humming their wings. Chick feeding intervals averaged twenty minutes. Without

exception the moms brooded their chicks through eight

nights. The ninth they spent somewhere other than on the

nest. Chicks at that age were feathered enough to regulate their own

temperatures. The two chicks were large enough by then that their little bodies

stretched the nest and filled it side to side, with their backs almost flush

with the nest's rim. This age, nine days, is the earliest observation of

youngsters humming their wings.

When the chicks were 21 to 22 days old, the mother hummers began

construction on a second nest while still feeding her first two nestlings.

Fledge time for the chicks was commonly 23 days, however

some where 24 or 25 days old before they left the nest. Individual chick fledge

time is probably tied to its level of nourishment. First flights were usually no

farther than the nearest branch. When the chicks were 21 to 22 days old, the mother hummers began

construction on a second nest while still feeding her first two nestlings.

Fledge time for the chicks was commonly 23 days, however

some where 24 or 25 days old before they left the nest. Individual chick fledge

time is probably tied to its level of nourishment. First flights were usually no

farther than the nearest branch.

|

|

|

Chick

making first flight. |

While continuing to work on their second nests, the busy mom

hummers located and fed the newly flying chicks through two to three days before

they were on their own. While building her second nest the

first egg often appeared during the time she was feeding her two fledged chicks.

The common view held by most ornithologists about hummingbirds reusing an old

nest is that they don't. We found a different answer. While continuing to work on their second nests, the busy mom

hummers located and fed the newly flying chicks through two to three days before

they were on their own. While building her second nest the

first egg often appeared during the time she was feeding her two fledged chicks.

The common view held by most ornithologists about hummingbirds reusing an old

nest is that they don't. We found a different answer.

One tree nest was reused by a different mom hummer almost before

it had time to cool from previous use. Two Hummingbird

House nesting sites were reused by different moms within a day or two after the

first chicks fledged. Those three nests were home to a total of 12 hummingbird

chicks during one nesting season. We think these nests were reused because they

were still intact and in good condition. Few hummingbird nests survive the

winter months, and those that do are so dilapidated they are not reusable.

However, we found several cases where a new nest was built on top of an old

nest. One site had a stack of four nests, probably covering four years. One of

the little hens nested a third time. Her third set of chicks were only a month

old before they pointed their little beaks south and hummed with her and their

siblings toward wintering grounds in Mexico. One tree nest was reused by a different mom hummer almost before

it had time to cool from previous use. Two Hummingbird

House nesting sites were reused by different moms within a day or two after the

first chicks fledged. Those three nests were home to a total of 12 hummingbird

chicks during one nesting season. We think these nests were reused because they

were still intact and in good condition. Few hummingbird nests survive the

winter months, and those that do are so dilapidated they are not reusable.

However, we found several cases where a new nest was built on top of an old

nest. One site had a stack of four nests, probably covering four years. One of

the little hens nested a third time. Her third set of chicks were only a month

old before they pointed their little beaks south and hummed with her and their

siblings toward wintering grounds in Mexico.

Some nests were exquisite, woven by hens that worked with great

skill. Others were less than perfect. Differences in

building skills likely resulted from first time nesters being less adept at nest

building than experienced moms. Some nests were exquisite, woven by hens that worked with great

skill. Others were less than perfect. Differences in

building skills likely resulted from first time nesters being less adept at nest

building than experienced moms.

Many times one

female would hover a short distance from another female that was busy with nest

building. The busy female invariably ran the intruder away.

However, when the busy female left to gather more building material, the

intruder would zip in and either steal nesting material, or hover all around the

nest as if inspecting the work, possibly to gain building skills of her own. It

also seemed as though an intruding female was considering a take over. In one

instance, during her first day of nest building one female was building six

nests simultaneously. Each was about 20 feet apart and all were on Hummingbird

House platforms. During the second day she narrowed her building activity to

three of the six. On the third day she cut her work down to two. On the fourth

day she abandoned work on one and finished the other during her fifth day. In

two other instances one female worked on two nests simultaneously before

abandoning one and finishing the other. Many times one

female would hover a short distance from another female that was busy with nest

building. The busy female invariably ran the intruder away.

However, when the busy female left to gather more building material, the

intruder would zip in and either steal nesting material, or hover all around the

nest as if inspecting the work, possibly to gain building skills of her own. It

also seemed as though an intruding female was considering a take over. In one

instance, during her first day of nest building one female was building six

nests simultaneously. Each was about 20 feet apart and all were on Hummingbird

House platforms. During the second day she narrowed her building activity to

three of the six. On the third day she cut her work down to two. On the fourth

day she abandoned work on one and finished the other during her fifth day. In

two other instances one female worked on two nests simultaneously before

abandoning one and finishing the other.

A roadrunner raided one New Mexico tree nest, ants killed two

day old chicks in another, and a Texas hailstorm destroyed

another. The Hummingbird House nesting sites had no weather

or predator problems. A roadrunner raided one New Mexico tree nest, ants killed two

day old chicks in another, and a Texas hailstorm destroyed

another. The Hummingbird House nesting sites had no weather

or predator problems.

Two nests became

unattended when the mothers apparently met with unknown fates. One mom had

collected fiberglass from somewhere and used the glass for lining her

nest. Two nests became

unattended when the mothers apparently met with unknown fates. One mom had

collected fiberglass from somewhere and used the glass for lining her

nest. We suspect she may have died from an overdose of fiberglass. In our

determination to not disturb the nesting process, we waited two days after her

disappearance to intervene. Her chicks were dead. After one full day of the

other mom's absence, we placed one of her starving orphans in an active

Black-chinned nest built on a Hummingbird House, and the other orphan in an

active Magnificent nest in a tree. What must have been two surprised hummingbird

mothers, both accepted and fed the third chicks. The second day after these

transfers, the Magnificent nest was empty and that mother not seen again. It is

probable the nest was raided by a predator. Meanwhile, back at the Hummingbird

House Black-chinned nest, three growing chicks soon created a space problem. The

two largest chicks crowded the smaller chick outside the nest, where it hung by

a tiny toenail hooked to spider webbing fourteen feet above the ground. The

problem was solved by installing the orphaned chick's "old" birth nest side by

side with its new nest and putting the toe-nail-hanging chick alone back in its

original nest. The mother continued to feed all three chicks and they all

fledged. We suspect she may have died from an overdose of fiberglass. In our

determination to not disturb the nesting process, we waited two days after her

disappearance to intervene. Her chicks were dead. After one full day of the

other mom's absence, we placed one of her starving orphans in an active

Black-chinned nest built on a Hummingbird House, and the other orphan in an

active Magnificent nest in a tree. What must have been two surprised hummingbird

mothers, both accepted and fed the third chicks. The second day after these

transfers, the Magnificent nest was empty and that mother not seen again. It is

probable the nest was raided by a predator. Meanwhile, back at the Hummingbird

House Black-chinned nest, three growing chicks soon created a space problem. The

two largest chicks crowded the smaller chick outside the nest, where it hung by

a tiny toenail hooked to spider webbing fourteen feet above the ground. The

problem was solved by installing the orphaned chick's "old" birth nest side by

side with its new nest and putting the toe-nail-hanging chick alone back in its

original nest. The mother continued to feed all three chicks and they all

fledged.

Although we learned lessons from tree

nests, we learned more from the Hummingbird House nests because they provided an

ambiance that allowed intimate observations from the nest's beginning to its end

. Although we learned lessons from tree

nests, we learned more from the Hummingbird House nests because they provided an

ambiance that allowed intimate observations from the nest's beginning to its end

.

To see a hummingbird nest in action, check under the porch

ceiling of County Line Barbeque in Albuquerque, New Mexico, between May 1 and

August 30. Two moms nested there on Hummingbird Houses in

the summer of 2000. Since hummers tend to return and breed in the area where

they were raised, if both little hens survive the winter, they should return to

the restaurant, along with surviving daughters in 2001. It is probable that

between 3 and 6 nests will be built and occupied there in the summer of 2001.

(Three hens returned and were nesting under County Line's porch ceiling as of

May 24, 2001.) The total number of nesting hummers from year to year in the

restaurant's developing hummingbird colony will depend on how many moms and

their daughters survive the winters. Extra Houses are in place for additional

moms. In 2002, there could be 6 to 10 hummingbirds raising chicks in nests under

County Line's porch. To see a hummingbird nest in action, check under the porch

ceiling of County Line Barbeque in Albuquerque, New Mexico, between May 1 and

August 30. Two moms nested there on Hummingbird Houses in

the summer of 2000. Since hummers tend to return and breed in the area where

they were raised, if both little hens survive the winter, they should return to

the restaurant, along with surviving daughters in 2001. It is probable that

between 3 and 6 nests will be built and occupied there in the summer of 2001.

(Three hens returned and were nesting under County Line's porch ceiling as of

May 24, 2001.) The total number of nesting hummers from year to year in the

restaurant's developing hummingbird colony will depend on how many moms and

their daughters survive the winters. Extra Houses are in place for additional

moms. In 2002, there could be 6 to 10 hummingbirds raising chicks in nests under

County Line's porch.

Hummingbird banders have established the average life-span of

female hummers to be 3 1/2 years. Average male life-span is 2 1/2. Black-chinned

record longevity is 7 years. Hummingbird banders have established the average life-span of

female hummers to be 3 1/2 years. Average male life-span is 2 1/2. Black-chinned

record longevity is 7 years.

The

longest Black-chinned migration on record is that of a male banded at Sonita,

Arizona, in July of 1988. In April of 1991, this little guy was recovered a few

miles NNW of Manzanillo, Mexico, 930 miles south of Sonita. This was the first

documented hummingbird flight linking the US and Mexico. Here's to many

more. The

longest Black-chinned migration on record is that of a male banded at Sonita,

Arizona, in July of 1988. In April of 1991, this little guy was recovered a few

miles NNW of Manzanillo, Mexico, 930 miles south of Sonita. This was the first

documented hummingbird flight linking the US and Mexico. Here's to many

more.

Happy humming.

Dan & Diane True

Authors of "Hummingbirds of North America".

May 24, 2001 update: Observations gained so far during

this 2001 nesting season have caused us to wonder: May 24, 2001 update: Observations gained so far during

this 2001 nesting season have caused us to wonder:

Picture this: A hen

heavy with eggs is looking for a place to build a nest. At the same time,

winds are blowing hard, gyrating tree branch nest sites so violently as to

make nest building difficult to impossible. Desperation, plus the urgency of

eggs about to arrive forces her to build on a porch light fixture, or other

device such as our Hummingbird House, neither of which is gyrating because

they are protected from the wind. Picture the same situation on a day with

steady rain. The urgency of eggs about to arrive forces her to search for a

nest site while it is raining. Trees are wet and dripping. Again, she finds a

porch light fixture, or our Hummingbird House, both of which are dry during

the rain. Being smart, she builds a nest there and successfully raises her

family.

|

HummerDome-8 oz

HummerDome-8 oz

Hummerfest Hummingbird Feeder-12 oz.

Hummerfest Hummingbird Feeder-12 oz.

Hummerfest Hummingbird Feeder-8 oz.

Hummerfest Hummingbird Feeder-8 oz.

Nectar Pot

Nectar Pot

Window-Mount Hummingbird Feeder-16 oz.

Window-Mount Hummingbird Feeder-16 oz.

Hummingbird House

Hummingbird House

Woodside Gardens

The Registry of Nature Habitats

Woodside Gardens

The Registry of Nature Habitats

1999 -

1999 -